By Kyle Hill |

January 2, 2014

What does a narcissistic flying reptile that loves the taste of crispy

dwarves have in common with a beetle that shoots hot, caustic liquid

from its butt? More than you think.

A few weeks ago, audiences were finally treated to the Cumberbatch-infused reptilian villain from J.R.R. Tolkien’s classic

The Hobbit.

Smaug (pronounced and interpreted as if you smashed together “smug” and

“smog”) is a terrible dragon that long ago forced a population of

dwarves from under a mountain. He laid claim to all their treasures. He

burned all their homes. The titular character of the book is then tasked

with helping a company of these displaced dwarves take back the

mountain from the beast. It wouldn’t be easy—the most common descriptor

of a dragon is “fire-breathing,” after all. But unlike other aspects of

the book and now the film that are wholly magic, Smaug’s burning breath

is actually one of the least magical, and can be wrangled into

plausibility. Doing so involves looking inside a beetle’s butt, a Boy

Scout’s satchel, and a bird’s throat.

Even though they don’t exist, dragons, like all other real organisms,

have evolved over time. They weren’t always so huge. Dragons were once

the size of cattle in popular depictions. And some of them didn’t have

wings, or breathe fire. Today’s dragons are uniquely terrible

lizards—massive, spiked, voracious, flame-spewing beasts. If even

mythical beasts evolve, how would a real dragon evolve its most

recognizable ability?

First, a dragon needs fuel.

This aspect of dragon fire is the easiest to imagine. In fact, you

are probably producing dragon fuel as you read this sentence. Methane—a

highly flammable gas that is produced naturally by bacteria in the

gut—is constantly bubbling up in your stomach as microbes munch on your

food. With a large stomach or even a separate organ to house this gas, a

dragon could easily eat enough food to produce a large amount of

methane.

If methane isn’t the fuel, another more exotic liquid might be. Take the bombardier beetle. This incredible insect evolved (

yes, evolved)

a way to harness the chaos of chemical reactions in a defense

mechanism. When under threat, the beetle excretes two chemicals from two

separate reservoirs that mix in a third, producing a very hot liquid

and the gas needed to

propel it into the face of some would-be predator.

When two liquids come together, react, and spontaneously combust,

they are called “hypergolic.” The bombardier beetle isn’t the only

organism that takes advantage of hypergolic chemicals; we use them in

rocket fuel. (You can see a nice small-scale demonstration of a

hypergolic reaction

here.) A dragon could do the same. It wouldn’t be the first fiction animal to do so either. Who can forget (or maybe remember?) the

giant, fire-spewing “tanker” bug from the ironically classic sci-fi movie

Starship Troopers?

If a

dragon convergently evolved chemicals that combust upon mixing, like the

explosive bombardier beetle, the reaction it harnessed could result in

fire…

terrible, terrible, fire.

But these chemicals aren’t cheap, biologically speaking. A dragon would

have to make a large biological investment to produce them. That would

at least be consistent with dragons’ voracious appetite for dwarves,

men, and livestock—the winged beasts need to produce more rocket fuel.

The next step in fire breathing is the spark.

Before you see a dragon’s flame you see the teeth. Terrifying spears

and stake knives that click and clamor inside gigantic mouths—giant

flints. Some dragon lore speculates that dragons, like modern birds,

ingested rocks and stones to aid in digestion. Over time, stories say,

the minerals would coat dragon teeth. Or maybe the dragons could hold

some minerals in their mouths. Either way, quickly biting down on these

minerals could produce a spark. Like a Boy Scout’s trusty flint,

clicking dragon teeth would provide the ignition for either a glut of

methane gas or a gush of hypergolic liquids (if needed).

Another possible spark could come from more detailed physics. If

dragon teeth had piezoelectric properties—where mechanical stress

produces small jolts of electricity—a combination of methane exhalation

and teeth grinding could light the fire. Or maybe the crushed stones and

minerals could vaporize in the air ahead of the methane and combust, as

metals do on helicopter rotors in

the Kopp-Etchells Effect.

Perhaps the dragons could expel the liquids or gases so quickly from

their bellies that static ignition would occur. (When cleaning out

supertankers, for example, all the flammable vapors first must be

vented. The high-pressure water jets used in cleaning can generate

sparks that ignite the gas.) Could a dragon evolve an organ that

produces its own spark like a kaiju from

Pacific Rim? Science has many sources of ignition to choose from, it’s just a matter of what the fiction allows.

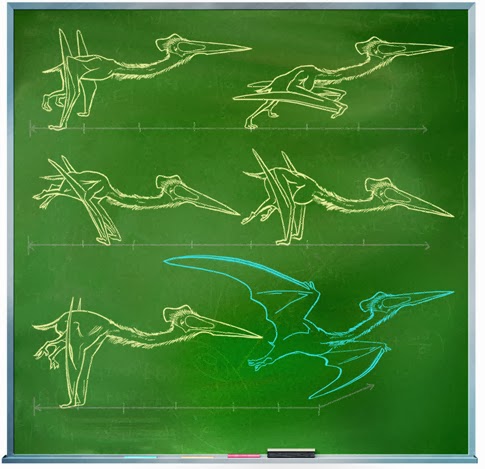

Dragons are basically our pipe-dreams of what birds would be if they

still looked liked ancient dinosaurs but followed evolution’s flight

plan. Dragons’ similarities with birds (themselves in fact dinosaurs)

could provide the last critical link to flame flinging. With multiple

stomachs aiding digestion, birds—and by extension, dragons—could evolve a

specialized sack for storing either methane or combustible chemicals.

Birds also eat stones and rocks to break up tough material in these

stomachs, so Smaug munching on minerals isn’t that far-fetched either.

There are still a few problems. Dragons are huge, undoubtedly heavy

creatures that would likely rip their own wings to shreds when

attempting to stay airborne. Also, holding both a large amount of

methane or hypergolic chemical internally is explosively problematic.

Breathing out fire is a problem in and of itself. A dragon would need

specialized tissues in the mouth to deal with the incredible heat, and

lungs large enough to force the flames a significant distance (unless it

was a dragon from

Skyrim, which specializes in powerful blasts

of voice). I imagine that a more scientifically plausible dragon

wouldn’t be the slender, monitor lizard-like monstrosity we see in the

latest

Hobbit film and more like a flightless, bloated flame-thrower.

What does this mean for

The Hobbit, a universe already filled with magic? Nothing at all.

The film has its own problems

to deal with. Nonetheless, I found Smaug’s fire breath to be one of the

least distressing suspensions of reality. Whether a “true”

fire-breathing dragon is filled with flint, gas, or rocket fuel, one

thing is for sure: Where there is Smaug, there is fire.

About the Author: Kyle Hill is a freelance science

writer and communicator who specializes in finding the secret science in

your favorite fandom. Follow on Twitter

@Sci_Phile.