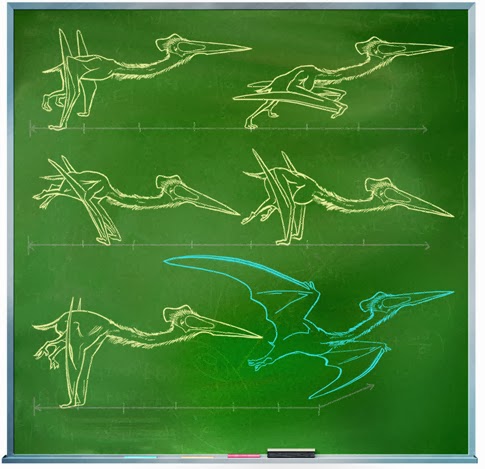

Illustration of the pterosaur quadrupedal launch. Appeared in Popular Science, credited to Kevin Hand (3 March 2009).

Rossella Lorenzi

Pterosaurs, the flying lizards of the dinosaur age,

ruled prehistoric skies with aerodynamic tricks like those found in

modern aircraft, according to a fossil study.

Like their dinosaur cousins, the creatures were affected by the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago, leaving no descendants.

Pterosaurs had light, hollow bones, but had wingspans up to 9 metres and more.

Indeed, fossilised bones recently found in Mexico suggest these creatures could have had a wingspan of at least 18 metres, the size of a plane.

Scientists have long wondered how these prehistoric jumbo jets could fly.

Now Dr Matthew Wilkinson of the University of Cambridge and colleagues report in the current issue of the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences that these flying reptiles could take off and make soft landings thanks to the animal's pteroid bone.

The pteroid bone's connected to the ...

The pteroid was a long, slender bone unique to pterosaurs, was bent at the wrist and supported a membranous forewing that acted as a large flap at the front of each wing.

Scientists have debated the function of this bone, particularly its position in the wing.

Fossil studies suggest that it pointed toward the body, and that the forewing was relatively narrow.

Other studies suggest it was directed forward during flight, resulting in a much broader forewing.

"It is not possible to resolve the debate about pteroid function using fossil evidence alone," the researchers write.

They tackled the problem a different way. Using wind tunnel tests of scale models of pterosaurs, the researchers compared the performances of each position of the pteroid bone.

"We discovered that lift is greatly increased if the pteroid bone pointed forwards in flight, not inwards as had been previously believed. This had the effect of expanding the skin-like forewing in front of the arm," says Wilkinson.

Just like plane flaps

The high lift would have been vital in allowing the largest pterosaurs to take off and land, in a similar way that flaps work on aircraft wings.

Large pterosaurs would have been able to take off simply by spreading their wings while facing a breeze. The leading edge flap would also have slowed landings, acting as an airbrake.

"It would have also served as a control surface during normal flights. For example, flexing one pteroid while extending the other would have increased lift on one wing, thereby initiating a roll," the researchers write.

According to UK dinosaur expert Darren Naish of the University of Portsmouth, the study "provides a new rigorous interpretation of pterosaur aerodynamics".

"This work solves several mysteries that have long existed, and shows that pterosaurs evolved novel solutions to the problems of active flight."

0 comments:

Post a Comment